ATLANTA — Florida was the first state to pass a law regulating the use of cellphones in schools in 2023. Just two years later, more than half of all states have laws in place, with more likely to act soon.

A ninth grader places his cellphone into a phone holder as he enters class at Delta High School on Feb. 23, 2024, in Delta, Utah.

Bills have sprinted through legislatures this year in states as varied as New York and Oklahoma, reflecting a broad consensus that phones are bad for kids.

Connecticut state Rep. Jennifer Leeper, a Democrat and co-chair of the General Assembly’s Education Committee, on May 13 called phones “a cancer on our kids” that are “driving isolation, loneliness, decreasing attention and having major impacts both on social-emotional well-being but also learning.”

Republicans express similar sentiments.

“This is a not just an academic bill,” Republican Rep. Scott Hilton said after Georgia's bill, which only bans phones in grades K-8, passed in March. “This is a mental health bill. It’s a public safety bill.”

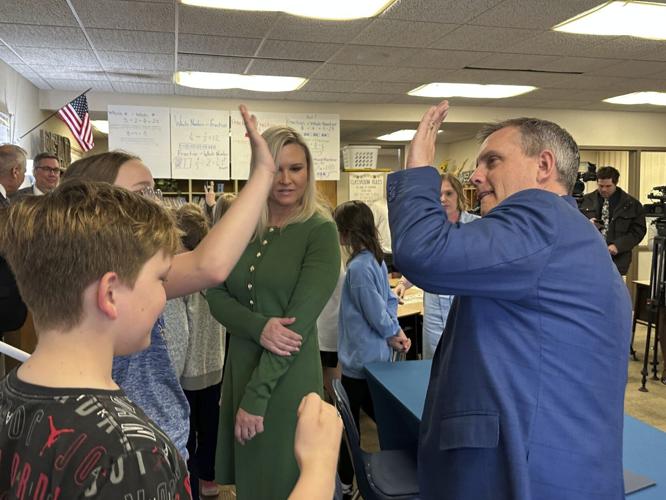

North Dakota Republican Gov. Kelly Armstrong, right, high-fives a student at Centennial Elementary School on April 25 in Bismarck, N.D., after he signed a bill for a "bell-to-bell" cellphone ban for public school K-12 students. At middle is first lady Kjersti Armstrong.

So far, 26 states have passed laws, with eight other states and the District of Columbia implementing rules or making recommendations to local districts. Of the states, 17 have acted this year. Just Tuesday, Nebraska Republican Gov. Jim Pillen signed a law banning phones throughout the school day. Earlier Tuesday, Alaska lawmakers required schools to regulate cellphones when they overrode an education package Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy vetoed for unrelated reasons.

More action is coming as bills await a governor's signature or veto in Florida, Missouri, Nebraska and New Hampshire.

When Florida first acted, lawmakers ordered schools to ban phones during instructional time while allowing them between classes or at lunch. But now there's another bill awaiting Gov. Ron DeSantis' action that would ban phones for the entire school day for elementary and middle schools.

Ten states and the District of Columbia have enacted school day bans, most for students in grades K-12, and they now outnumber the seven states with instructional time bans.

North Dakota Republican Gov. Kelly Armstrong called the ban throughout the school day that he signed into law “a huge win."

“Teachers wanted it. Parents wanted it. Principals wanted it. School boards wanted it," Armstrong said.

Armstrong recently visited a grade school with such a ban in place. He said he saw kids engaging with each other and laughing at tables during lunch.

The “bell-to-bell” bans have been promoted in part by ExcelinEd, the education think tank founded by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush. The group’s political affiliate has been active in lobbying for bans.

Nathan Hoffman, ExcelinEd's senior director of state policy and advocacy, said barring phones throughout the day heads off problems outside of class, like when students set up or record fights in halls.

“That’s often when you get some of your biggest behavioral issues, whether they go viral or not,” Hoffman said.

But other states, particularly where there are strong traditions of local school control, are mandating only that school districts adopt some kind of cellphone policy, believing districts will take the hint and sharply restrict phone access. In Maine, where some lawmakers originally proposed a school day ban, lawmakers are now considering a rewritten bill that would only require a policy.

And there have been a few states where lawmakers failed to act at all. Maybe the most dramatic was in Wyoming, where senators voted down a bill in January, with some opponents saying teachers or parents should set the rules.

Where policymakers have moved ahead, there's a growing consensus around exceptions. Most states are letting students use electronic devices to monitor medical needs and meet the terms of their special education plans. Some are allowing exceptions for translation devices if English isn't a student's first language or when a teacher wants students to use devices for classwork.

There are some unusual exceptions, too. South Carolina's original policy allowed an exception for students who are volunteer firefighters. West Virginia's new law allows smartwatches as long as they are not being used for communication.

But by far the most high-profile exception has been allowing cellphone use in case of emergencies. One of the most common parent objections to a ban is that they would not be able to contact their child in a crisis like a school shooting.

“It was only through text messages that parents knew what was happening," said Tinya Brown, whose daughter is a freshman at Apalachee High School, northeast of Atlanta, where a shooting killed two students and two teachers in September. She spoke against Georgia's law at a news conference in March.

Some laws call for schools to find other ways for parents to communicate with their children at schools, but most lawmakers say they support giving students access to their cellphones, at least after the immediate danger has passed, during an emergency.

In some states, students have testified in favor of regulations, but it's also clear that many students, especially in high schools, are chafing under the rules. Kaytlin Villescas, a sophomore at Prairieville High School, in the suburbs of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, is one student who took up the fight against bans, starting a petition and telling WBRZ-TV in August that Louisiana's law requiring a school day ban is misguided. She argued that schools should instead teach responsible use.

“It is our proposition that rather than banning cellphone use entirely, schools should impart guidelines on responsible use, thereby building a culture of respect and self-regulation,” Villescas wrote in an online petition.

'Alarming' national data: Teens use cellphones for quarter of school day

'Alarming' national data: Teens use cellphones for quarter of school day

Updated

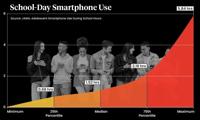

As districts and government officials nationwide consider curbing smartphones' reach, new research has revealed teens miss at least one and a half hours of school because they are on their phones.

A quarter of the 13-18-year-olds in the study used devices for two hours each school day, which lasts around seven hours. The averages outnumber minutes allotted for lunch and period breaks combined, showing youth are distracted by phones throughout huge chunks of class time.

Teen Phone Use in School Raises Learning and Social Concerns

Updated

Stony Brook University's research, published in JAMA Pediatrics, is the first to accurately paint a picture of adolescent phone behavior by using a third party app to monitor usage over four months in 2023. Previous studies have relied on parent surveys or self-reported estimates.

"That's pretty alarming … It's too much, not only because of the missed learning opportunity in the classroom," said researcher Lauren Hale, sleep expert and professor at Stony Brook's Renaissance School of Medicine.

"They're missing out on real life social interaction with peers, which is just as valuable for growth during a critical period of one's life," she told The 74.

Hale and the other researchers' early findings come from 117 teens for which they had school data, just one slice of a pool from over 300 participants, which will be analyzed and used to consider how phone usage impacts sleep, obesity, depression, and other outcomes.

Teens most often used messaging, Instagram and video streaming platforms. While most spent about 26 minutes on Instagram, in one extreme case, a student was on the app for 269 minutes—nearly 5 hours—during the school day.

Data reveal particular groups of students are using their phones more than their peers: Girls and older kids, aged 16 to 18, spent a half hour above the average 1.5 hours; and Latino and multiracial students spent on average 15 minutes above average.

Additionally, though researchers cannot hypothesize as to why based on the descriptive data, kids who have one or more parents with a college degree used smartphones less during the school day.

The findings are particularly concerning given young people missed key social years with peers during the pandemic, the impact of which is felt in ways big and small, like being hesitant to work with peers in groups.

Teachers in contact with Hale since research went public in early February said of the 1.5 hour average, "that's too low an estimate. They think we underestimated."

Los Angeles is among several districts with plans to institute a cellphone ban, though such bans are inconsistently implemented and new research from the U.K. suggests bans alone do not impact grades or wellbeing.

"These results are consistent, supportive evidence of anecdotal stories from across the country about kids missing out on learning and social opportunities. [They] can help justify efforts to provide a coherent smartphone policy for schools," said Hale, adding that such policy should not be left up to individual teachers to enforce.

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

COPYRIGHT 2025 BY KOAM NEWS NOW. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS MATERIAL MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, REWRITTEN OR REDISTRIBUTED.